Communication and Reducibility

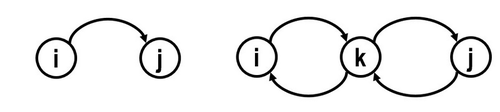

Before moving on and discovering more behaviors of Markov chains, we need to classify the properties of states first. In the previous section, we use $ P_{ij} $ to represent the transition probability of state changing from $ i $ to $ j $; now, we use $ P_{ij}^{n} $ to denote the transition probability of state changing from $ i $ to $ j $ after $ n $ step. If $ P_{ij}^{n} \geq 0 $ for all $ n \geq 1 $, we say state $ j $ is accessible from state $ i $, which also can be written as $ i \rightarrow j $. If $ i \rightarrow j $ and at the same time $ j \rightarrow i $, then we say that state $ i $ and state $ j $ communicate, which can be denoted as $ i \leftrightarrow j $. On the other hand, if $ P_{ij}^{n} = 0 $ or $ P_{ji}^{n} = 0 $, or if both of them come into existence, we claim that state $ i $ and state $ j $ do not communicate. The diagrams below illustrate these two cases.

If all states of a Markov chain belong to one communication class, then that Markov chain is considered irreducible. If there are two or more communication classes, we call that Markov chain reducible.

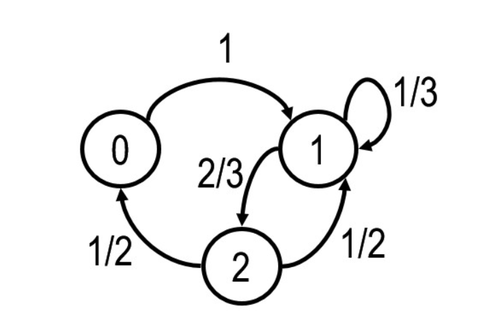

An example of the Irreducible Markov chains:

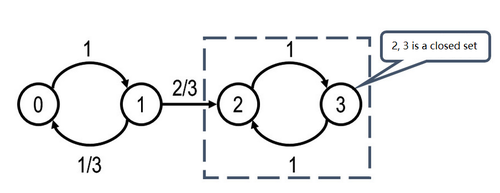

An example of reducible Markov chains:

From the above diagram, we can see that after transiting from state 1 to state 2, the state 2 and 3 become a closed set; namely, they are never going to return to state 1; therefore, we can say it is a reducible Markov chain.

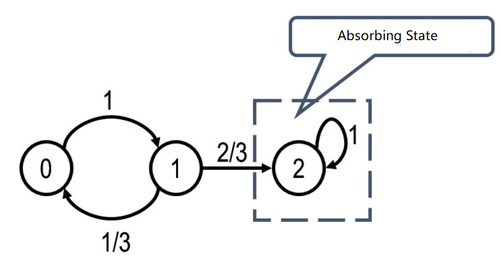

Another example of reducible Markov chain:

Similarly, after transiting from state 1 to 2, state 2 will never return to state 1.