Convolution

Convolution is often presented in a manner that emphasizes efficient calculation over comprehension of the convolution itself. To calculate in a pointwise fashion, we're told: "flip one of the input signals, and perform shift+multiply+add operations until the signals no longer overlap." This is numerically valid, but you could in fact calculate the convolution without flipping either signals. We'll perform the latter here for illustration. Consider the convolution of the following constant input and causal impulse reponse:

$ y[n] \,=\, x[n] \ast h[n] $

$ x[n] \,=\, 1 \;\;\;\;\; \forall \, n $

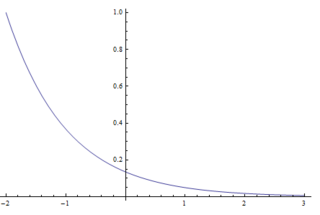

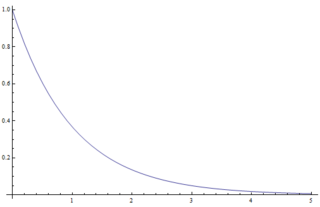

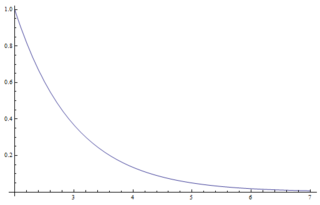

$ h[n] = \left\{ \begin{array}{lr} \mathrm{e}^{-n} & : n \geq 0\\ 0 & : n < 0 \end{array} \right. $

Our input function x is a constant 1. You can think of this as a delta function occurring at every discrete time step, and therefore causing the impulse reponse to 'go off' at every time step (see graphs below for better visualization). What we term the 'convolution' is just the summation of all these time-shifted impulse reponses at the time we want to find the convolution for (ie time n for y[n]). To more tangibly express 'summation of all these time-shifted impulse reponses', we can consider an impulse that was generated at time n=0. We know that output from that singular impulse response should be $ (1)(e^{0}) = 1 $ at n=0, $ (1)(e^{-1}) = e^{-1} $ at n=1, $ (1)(e^{-2}) = e^{-2} $ at n=2, and so on. But because we have a constant input signal that effectively serves as a delta function at each time step, another impulse would be generated at n=1, yielding $ (1)(0) = 0 $ at n=0, $ (1)(e^{0}) = 1 $ at n=1, $ (1)(e^{-1}) = e^{-1} $ at n=2, and so on. Look at what's occurring at n=1 here: the convolution will yield $ 1 + e^{-1} $ for the two impulse responses started at time n=0 and n=1. But if we carry this back to earlier impulse responses, we see that we get the geometric series:

$ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \mathrm{e}^{-k} \,=\, 1 + \frac{1}{e} + \frac{1}{e^2} + \frac{1}{e^3} + ... \,=\, \frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{e}} \,\approx\, 1.582 $

Without even resorting to the convolution formula given to us in class, we intuitively grasped what the convolution should be for any time n (doesn't matter what n we choose since input has always been and will always be the same), and calculated the output y[n] for all n. Again to clarify, the impulse response calculated here was just the (additive) superposition of time-shifted impulse functions. And because our input is 1 for all n, each of those superimposed impulse responses is scaled with constant coefficient of 1, simplifying our computation to a geometric series.

Now that we've figured out the discrete time case, let's consider the continuous case of these same input and impulse response functions, now defined for all t instead of at discrete intervals n. Using the same intuition as before, in which we consider additive superposition of identically scaled but time-shifted impulse response, we see that instead of having a countably infinite number of values to add (eg $ 1, e^{-1}, e^{-2}, ... $), we now have an uncountably infinite number of values to add (starting with 1, $ 1^-, ... $).

It should soon become clear that this infinite summation of inifinitesimally smaller values would yield an infinite or undefined result. (See equations below for mathematical explanation.) If this is not intuitively clear to you, consider that there are an infinite number of values between .9 and 1 in the continuous impulse response we defined above. Therefore (.9)(infiniti), which is infinite, is a lower bound for the convolution at any y(t). Therefore y(t) is infinite.

Note that even if we defined our input as teh heaviside step function instead of a constant signal, the resulting convolution for non-negative time would only be finite at t=0, where y(t=0) would equal 1. Perhaps you could argue that $ y(t=0^+) = 2 $, but moving further, we observe that our constant input has generated an infinite number of impulse responses. This leads to an interesting conclusion: an integrable discrete-time convolution may not be integrable in continuous time.

actually, i think i confused myself here. i don't understand why these convolutions are not coming out to be infinite (or should they be finite?).

$ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} h(\tau)\,\mathrm{d}\tau \,=\, \int_{0}^{\infty} h(\tau)\,\mathrm{d}\tau \;\;\;\;\; \because h(t)=0 \;\;\; \forall \, t<0 $

$ \Rightarrow \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{e}^{-\tau}\,\mathrm{d}\tau \,=\, \left.-\mathrm{e}^{-\tau}\right|_{0}^{\infty} \,=\, -(\mathrm{e}^{-\infty} - \mathrm{e}^{0}) \,=\, -(0 - 1) \,=\, 1 $

$ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} h(t-\tau)\,\mathrm{d}\tau \,=\, \int_{-\infty}^{t} h(t-\tau)\,\mathrm{d}\tau \;\;\;\;\; \because h(t)=0 \;\;\; \forall \, t<0 $

$ \Rightarrow \int_{-\infty}^{t} \mathrm{e}^{-(t-\tau)}\,\mathrm{d}\tau \,=\, \int_{-\infty}^{t} \mathrm{e}^{\tau-t}\,\mathrm{d}\tau \,=\, \left.\mathrm{e}^{\tau-t}\right|_{-\infty}^{t} \,=\, \mathrm{e}^{0} - \mathrm{e}^{-\infty-t} \;\; (\forall \, t>0) \,=\, 1 - 0 \,=\, 1 $