| (145 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | ''' | + | '''Implementation of the Divide and Conquer DFT via Matrices''' |

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

BY: Cary A. Wood | BY: Cary A. Wood | ||

| + | </span> | ||

<span> | <span> | ||

| − | The purpose of this article is to illustrate the differences of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) versus the | + | The purpose of this article is to illustrate the differences of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) versus the Divide and Conquer Discrete Fourier Transform (dcDFT). In addition, it will provide a further explanation of the dcDFT calculation path as described in Lab 6 (Week 2, pg. 5) of ECE 438. The link can be found here [https://engineering.purdue.edu/VISE/ee438L/lab6/pdf/lab6b.pdf]. Please note the following explanation assumes the user understands the basic concepts of the Discrete Fourier Transform. |

</span> | </span> | ||

| Line 13: | Line 16: | ||

<span> | <span> | ||

| − | It is fairly easy to visualize this 1 point DFT, but how does it look when x[n] has 8 points, 1024 points, etc. That's where matrices come in. For an N point DFT, we will define our input as x[n] where n = 0, 1, 2, ... N-1. Similarly, the output will be defined as X[k] where k = 0, 1, 2, ... N-1. Referring to our definition of the Discrete Fourier Transform above, to compute an N point DFT, all we need to do is simply repeat Eq. 1 N times. For every value of x[n] in the discrete time domain, there is a corresponding value, X[k]. | + | It is fairly easy to visualize this 1 point DFT, but how does it look when x[n] has 8 points, 1024 points, etc. That's where matrices come in. For an N point DFT, we will define our input as x[n] where n = 0, 1, 2, ... N-1. Similarly, the output will be defined as X[k] where k = 0, 1, 2, ... N-1. Referring to our definition of the Discrete Fourier Transform above, to compute an N point DFT, all we need to do is simply repeat Eq. 1, N times. For every value of x[n] in the discrete time domain, there is a corresponding value, X[k], in the frequency domain. |

</span> | </span> | ||

<span> | <span> | ||

| − | ''Input'' x[n] | + | ''Input'' x[n] = |

</span> | </span> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\begin{bmatrix} | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| − | x[0] & x[1] & {\dotsb} & x[N-1] | + | x[0] & x[1] & {\;}{\dotsb} & x[N-1] |

\end{bmatrix} | \end{bmatrix} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

<span> | <span> | ||

| − | ''Output'' X[k] | + | ''Output'' X[k] = |

</span> | </span> | ||

| Line 55: | Line 58: | ||

= | = | ||

x[0]\begin{bmatrix} | x[0]\begin{bmatrix} | ||

| − | e^{-j2{\pi}(0) | + | e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ |

| − | e^{-j2{\pi}(0) | + | e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ |

| − | e^{-j2{\pi}(0) | + | e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ |

{\vdots} \\ | {\vdots} \\ | ||

| − | e^{-j2{\pi}(0) | + | e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} |

\end{bmatrix} | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| Line 83: | Line 86: | ||

+ | + | ||

| + | {\;} | ||

{\dotsb} | {\dotsb} | ||

| + | {\;} | ||

+ | + | ||

| Line 94: | Line 99: | ||

\end{bmatrix} | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| − | Eq. 2 | + | {\;} {\;} (Eq. 2) |

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 101: | Line 106: | ||

From this matrix representation of the DFT, you can see that N^2 complex multiplications and N^2 - N complex additions are necessary to fully compute the discrete fourier transform. There are a few simplifications that can be made right away. The first column vector of complex exponentials can be reduced to a vector of 1's. This is possible because, e^(0*anything) will always equal 1. This also applies for the first entry in each vector of complex exponentials because n always begins at 0. | From this matrix representation of the DFT, you can see that N^2 complex multiplications and N^2 - N complex additions are necessary to fully compute the discrete fourier transform. There are a few simplifications that can be made right away. The first column vector of complex exponentials can be reduced to a vector of 1's. This is possible because, e^(0*anything) will always equal 1. This also applies for the first entry in each vector of complex exponentials because n always begins at 0. | ||

| − | + | Now whats happens when we want to perform the DFT on 3 minute audio signal recorded at a 44.1 kHz sampling rate? Our handy-dandy DFT suddenly becomes extremely lengthy since computation time increases with a rate of N^2 + (N^2-N). Due to the work of Cooley and Turkey (although previously discovered by Gauss), the development of the Fast Fourier Transform has reduced computation time by orders of magnitude. | |

</span> | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Introduction of the Divide and Conquer Method''' | ||

<span> | <span> | ||

| − | + | One of the key building blocks of the Fast Fourier Transform, is the Divide and Conquer DFT. As the name implies, we will divide Eq. 1 into two separate summations. The first summation processes the even components of x[n] while the second summation processes the odd components of x[n]. This produces, | |

| + | </span> | ||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | X_N[k] = \sum_{m=0}^{{N/2}-1} x[2m] e^{-j2{\pi}k(m)/(N/2)} | ||

| + | |||

| + | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | e^{-j2{\pi}k/N}\sum_{m=0}^{{N/2}-1} x[2m+1] e^{-j2{\pi}k(m)/(N/2)} | ||

| + | {\;} {\;} (Eq. 3) | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | Our DFT has now been successfully split into two N/2 pt DFT's. For simplification purposes, the first summation will be defined as X0[k] and the second summation as X1[k]. We can now simplify Eq. 3 to the following form. | ||

</span> | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | X[k] | ||

| + | = | ||

| + | X_0[k] | ||

| + | + | ||

| + | e^{-j2{\pi}k/n}X_1[k] {\;} {\;} {\;} (Eq. 4) | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | The complex exponential preceding X1[k] in Eq. 3 is generally called the "twiddle factor" and represented by | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | {W_N}^k = e^{-j2{\pi}k/N} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | By definition of the discrete fourier transform, X0[k] and X1[k] are periodic with period N/2. Therefore we can split Eq. 3 into two separate equations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | X[k] | ||

| + | = | ||

| + | X_0[k] | ||

| + | + | ||

| + | {{W_N}^k}X_1[k] | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | X[k+(N/2)] | ||

| + | = | ||

| + | X_0[k] | ||

| + | - | ||

| + | {{W_N}^k}X_1[k] | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | Once again were are left with a number of 1 pt. DFT's. So how do represent this in matrix form? First, note that we have two separate equations and therefore need two separate equations of matrices. Similar to Eq. 2, we will repeat the DFT for the entire length of the input signal. However, since we split x[n] into even and odd components, we will only repeat the DFT (N/2) times for X0 and X1. The first equation solves for the first half of X[k]. | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Eq. 5 and 6, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m) \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}(1)2m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}(2)2m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | {\vdots} \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}({N/2}-1)2m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| + | |||

| + | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | {W_N}^0 & 0 & {\dotsb} & 0 \\ | ||

| + | 0 & {W_N}^1 & & {\vdots} \\ | ||

| + | {\vdots} & & {W_N}^2 & \\ | ||

| + | & & {\ddots} & 0 \\ | ||

| + | 0 & {\dotsb} & & {W_N}^{(N/2)-1} | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| + | |||

| + | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1) \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | {\vdots} \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| + | |||

| + | = | ||

| + | |||

| + | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | X[0] \\ | ||

| + | X[1] \\ | ||

| + | X[2] \\ | ||

| + | {\vdots} \\ | ||

| + | X[{N/2}-1] | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | The second equation solves for the second half of X[k]. | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m) \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}(1)2m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}(2)2m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | {\vdots} \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}({N/2}-1)2m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| + | |||

| + | - | ||

| + | |||

| + | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | {W_N}^0 & 0 & {\dotsb} & 0 \\ | ||

| + | 0 & {W_N}^1 & & {\vdots} \\ | ||

| + | {\vdots} & & {W_N}^2 & \\ | ||

| + | & & {\ddots} & 0 \\ | ||

| + | 0 & {\dotsb} & & {W_N}^{(N/2)-1} | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| + | |||

| + | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1) \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | {\vdots} \\ | ||

| + | \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| + | |||

| + | = | ||

| + | |||

| + | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | X[N/2] \\ | ||

| + | X[(N/2)+1] \\ | ||

| + | X[(N/2)+2] \\ | ||

| + | {\vdots} \\ | ||

| + | X[N-1] | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | After analyzing the two matrices above, there are a few concepts you should understand. | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | 1) The matrix X0 in each equation is just the condensed form of Eq. 2 and then cut in half. It is simply the DFT repeated (N/2) times where the input is the even indices of x[n]. | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | 2) The matrix X1 in each equation, is also the condensed form of Eq. 2 cut in half. However, the input is now the odd indices of x[n]. | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | The equations below are the same as Eq. 5 and 6, but X0 and X1 are expressed in a simplified format. | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | Now compare these two equations to the dcDFT signal path below, as shown in Week 2 of Lab 6. | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:HW5Q1fig1.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | As you can see from image above, the signal path image from Lab 6 is derived directly from the two matrix equations above (Eq. 5 and 6). Although matrices X0 and X1 are used in both equations, they only need to be calculated once. X0 and X1 are calculated separately, and then combined to form the full vector X[k]. Hopefully this gives you a better idea of how to visualize the map given above. Below is example Matlab code of how to implement the DFT and dcDFT. | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''' DFT ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | function [X] = DFT(x) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | %DFT This function implements the Discrete Fourier Transform. | ||

| + | % input = x of length N (time) | ||

| + | % output = X of same length N (frequency) | ||

| + | % Authors: Cary Wood, Bill Gu | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | N = length(x); %find length of input vector | ||

| + | X(N) = 0; %initialize zero vector X(k) | ||

| + | for k = 1:N | ||

| + | for n = 1:N | ||

| + | X(k) = X(k) + x(n)*exp(-1j*2*pi*(k-1)*(n-1)/N); | ||

| + | end %end for | ||

| + | end %end for | ||

| + | |||

| + | end %end DFT | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''' dcDFT ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | function [X] = dcDFT(x) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span> | ||

| + | %dcDFT This function implements the Divide and Conquer Discrete Fourier Transform | ||

| + | % input = x of length N (time) | ||

| + | % output = X of same length N (frequency) | ||

| + | % Authors: Cary Wood, Bill Gu | ||

| + | </span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | N = length(x); %find length of input vector | ||

| + | |||

| + | x0 = x(1:2:N); %even components | ||

| + | x1 = x(2:2:N); %odd components | ||

| + | |||

| + | X0 = DFT(x0); %calculate X0 once | ||

| + | X1 = DFT(x1); %calculate X1 once | ||

| + | |||

| + | for k = 0:N/2-1 | ||

| + | W(k+1) = exp(-1j*2*pi*k/N); %calculate twiddle factor "W" | ||

| + | X(k+1) = X0(k+1) + W(k+1)*X1(k+1); %X0 + W*X1 | ||

| + | X(k+1+N/2) = X0(k+1) - W(k+1)*X1(k+1); %X0 - W*X1 | ||

| + | end %end for | ||

| + | |||

| + | end %end dcDFT | ||

Latest revision as of 07:25, 28 October 2013

Implementation of the Divide and Conquer DFT via Matrices

BY: Cary A. Wood

The purpose of this article is to illustrate the differences of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) versus the Divide and Conquer Discrete Fourier Transform (dcDFT). In addition, it will provide a further explanation of the dcDFT calculation path as described in Lab 6 (Week 2, pg. 5) of ECE 438. The link can be found here [1]. Please note the following explanation assumes the user understands the basic concepts of the Discrete Fourier Transform.

To start, we will define the DFT as,

$ X_N[k] = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} x[n] e^{-j2{\pi}kn/N} {\;} {\;} (Eq. 1) $

It is fairly easy to visualize this 1 point DFT, but how does it look when x[n] has 8 points, 1024 points, etc. That's where matrices come in. For an N point DFT, we will define our input as x[n] where n = 0, 1, 2, ... N-1. Similarly, the output will be defined as X[k] where k = 0, 1, 2, ... N-1. Referring to our definition of the Discrete Fourier Transform above, to compute an N point DFT, all we need to do is simply repeat Eq. 1, N times. For every value of x[n] in the discrete time domain, there is a corresponding value, X[k], in the frequency domain.

Input x[n] =

$ \begin{bmatrix} x[0] & x[1] & {\;}{\dotsb} & x[N-1] \end{bmatrix} $

Output X[k] =

$ \begin{bmatrix} X[0] \\ X[1] \\ {\vdots} \\ X[N-1] \end{bmatrix} $

To solve for X[K], means simply repeating Eq. 1, N times, where x[n] is a real scalar value for each entry. We represent this in the matrices below.

$ \begin{bmatrix} X[0] \\ X[1] \\ X[2] \\ {\vdots} \\ X[N-1] \end{bmatrix} = x[0]\begin{bmatrix} e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ {\vdots} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \end{bmatrix} + x[1]\begin{bmatrix} e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(1)/N} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(2)/N} \\ {\vdots} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(N-1)/N} \end{bmatrix} + x[2]\begin{bmatrix} e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(2)/N} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(4)/N} \\ {\vdots} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}2(N-1)/N} \end{bmatrix} + {\;} {\dotsb} {\;} + x[N-1]\begin{bmatrix} e^{-j2{\pi}(0)/N} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}(N-1)/N} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}2(N-1)/N} \\ {\vdots} \\ e^{-j2{\pi}{(N-1)^2}/N} \end{bmatrix} {\;} {\;} (Eq. 2) $

From this matrix representation of the DFT, you can see that N^2 complex multiplications and N^2 - N complex additions are necessary to fully compute the discrete fourier transform. There are a few simplifications that can be made right away. The first column vector of complex exponentials can be reduced to a vector of 1's. This is possible because, e^(0*anything) will always equal 1. This also applies for the first entry in each vector of complex exponentials because n always begins at 0.

Now whats happens when we want to perform the DFT on 3 minute audio signal recorded at a 44.1 kHz sampling rate? Our handy-dandy DFT suddenly becomes extremely lengthy since computation time increases with a rate of N^2 + (N^2-N). Due to the work of Cooley and Turkey (although previously discovered by Gauss), the development of the Fast Fourier Transform has reduced computation time by orders of magnitude.

Introduction of the Divide and Conquer Method

One of the key building blocks of the Fast Fourier Transform, is the Divide and Conquer DFT. As the name implies, we will divide Eq. 1 into two separate summations. The first summation processes the even components of x[n] while the second summation processes the odd components of x[n]. This produces,

$ X_N[k] = \sum_{m=0}^{{N/2}-1} x[2m] e^{-j2{\pi}k(m)/(N/2)} + e^{-j2{\pi}k/N}\sum_{m=0}^{{N/2}-1} x[2m+1] e^{-j2{\pi}k(m)/(N/2)} {\;} {\;} (Eq. 3) $

Our DFT has now been successfully split into two N/2 pt DFT's. For simplification purposes, the first summation will be defined as X0[k] and the second summation as X1[k]. We can now simplify Eq. 3 to the following form.

$ X[k] = X_0[k] + e^{-j2{\pi}k/n}X_1[k] {\;} {\;} {\;} (Eq. 4) $

The complex exponential preceding X1[k] in Eq. 3 is generally called the "twiddle factor" and represented by

$ {W_N}^k = e^{-j2{\pi}k/N} $

By definition of the discrete fourier transform, X0[k] and X1[k] are periodic with period N/2. Therefore we can split Eq. 3 into two separate equations.

$ X[k] = X_0[k] + {{W_N}^k}X_1[k] $

$ X[k+(N/2)] = X_0[k] - {{W_N}^k}X_1[k] $

Once again were are left with a number of 1 pt. DFT's. So how do represent this in matrix form? First, note that we have two separate equations and therefore need two separate equations of matrices. Similar to Eq. 2, we will repeat the DFT for the entire length of the input signal. However, since we split x[n] into even and odd components, we will only repeat the DFT (N/2) times for X0 and X1. The first equation solves for the first half of X[k].

Eq. 5 and 6,

$ \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m) \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}(1)2m/(N/2)} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}(2)2m/(N/2)} \\ {\vdots} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}({N/2}-1)2m/(N/2)} \\ \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} {W_N}^0 & 0 & {\dotsb} & 0 \\ 0 & {W_N}^1 & & {\vdots} \\ {\vdots} & & {W_N}^2 & \\ & & {\ddots} & 0 \\ 0 & {\dotsb} & & {W_N}^{(N/2)-1} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1) \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ {\vdots} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} X[0] \\ X[1] \\ X[2] \\ {\vdots} \\ X[{N/2}-1] \end{bmatrix} $

The second equation solves for the second half of X[k].

$ \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m) \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}(1)2m/(N/2)} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}(2)2m/(N/2)} \\ {\vdots} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m)e^{-j2{\pi}({N/2}-1)2m/(N/2)} \\ \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} {W_N}^0 & 0 & {\dotsb} & 0 \\ 0 & {W_N}^1 & & {\vdots} \\ {\vdots} & & {W_N}^2 & \\ & & {\ddots} & 0 \\ 0 & {\dotsb} & & {W_N}^{(N/2)-1} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1) \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ {\vdots} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{{N/2}-1} x(2m+1)e^{-j2{\pi}m/(N/2)} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} X[N/2] \\ X[(N/2)+1] \\ X[(N/2)+2] \\ {\vdots} \\ X[N-1] \end{bmatrix} $

After analyzing the two matrices above, there are a few concepts you should understand.

1) The matrix X0 in each equation is just the condensed form of Eq. 2 and then cut in half. It is simply the DFT repeated (N/2) times where the input is the even indices of x[n].

2) The matrix X1 in each equation, is also the condensed form of Eq. 2 cut in half. However, the input is now the odd indices of x[n].

The equations below are the same as Eq. 5 and 6, but X0 and X1 are expressed in a simplified format.

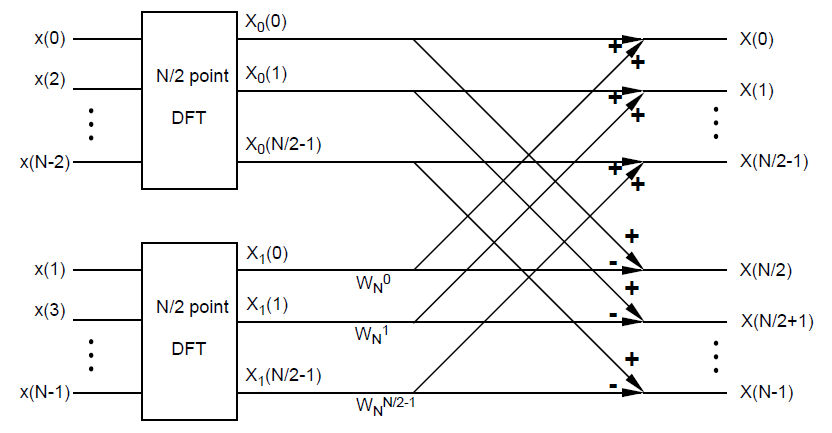

Now compare these two equations to the dcDFT signal path below, as shown in Week 2 of Lab 6.

As you can see from image above, the signal path image from Lab 6 is derived directly from the two matrix equations above (Eq. 5 and 6). Although matrices X0 and X1 are used in both equations, they only need to be calculated once. X0 and X1 are calculated separately, and then combined to form the full vector X[k]. Hopefully this gives you a better idea of how to visualize the map given above. Below is example Matlab code of how to implement the DFT and dcDFT.

DFT

function [X] = DFT(x)

%DFT This function implements the Discrete Fourier Transform. % input = x of length N (time) % output = X of same length N (frequency) % Authors: Cary Wood, Bill Gu

N = length(x); %find length of input vector X(N) = 0; %initialize zero vector X(k) for k = 1:N

for n = 1:N

X(k) = X(k) + x(n)*exp(-1j*2*pi*(k-1)*(n-1)/N);

end %end for

end %end for

end %end DFT

dcDFT

function [X] = dcDFT(x)

%dcDFT This function implements the Divide and Conquer Discrete Fourier Transform % input = x of length N (time) % output = X of same length N (frequency) % Authors: Cary Wood, Bill Gu

N = length(x); %find length of input vector

x0 = x(1:2:N); %even components x1 = x(2:2:N); %odd components

X0 = DFT(x0); %calculate X0 once X1 = DFT(x1); %calculate X1 once

for k = 0:N/2-1

W(k+1) = exp(-1j*2*pi*k/N); %calculate twiddle factor "W" X(k+1) = X0(k+1) + W(k+1)*X1(k+1); %X0 + W*X1 X(k+1+N/2) = X0(k+1) - W(k+1)*X1(k+1); %X0 - W*X1

end %end for

end %end dcDFT