(New page: Category:math Category:math squad Category:tutorial Category:series == Geometric Series == by Alec McGail, proud Member of [[Math_squad | the Math Squad...) |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Category:tutorial]] | [[Category:tutorial]] | ||

[[Category:series]] | [[Category:series]] | ||

| + | [[Category:geometric series]] | ||

== Geometric Series == | == Geometric Series == | ||

by [[user:amcgail | Alec McGail]], proud Member of [[Math_squad | the Math Squad]]. | by [[user:amcgail | Alec McGail]], proud Member of [[Math_squad | the Math Squad]]. | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | |||

'''INTRODUCTION''' A geometric series is a very useful infinite sum which seems to pop up everywhere: | '''INTRODUCTION''' A geometric series is a very useful infinite sum which seems to pop up everywhere: | ||

| − | + | If <math>|r|<1</math>, | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math>a+ar+ar^2+ar^3+ar^4+\cdots=\frac{a}{1-r}</math>. | |

| + | |||

| + | In this tutorial, I will explain exactly what this formula means, why it's true, and how to use it. | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | == | + | ==Explanation== |

| − | + | If you fully understand what the above statement means, you may skip this section. If you've ever worked with infinite sums, you probably have some idea of what the "<math>\cdots</math>" is trying to imply. It's important, however, to know that mathematically, the expression | |

| − | <math> | + | <math>a_1 + a_2 + a_3 + \cdots</math> |

| − | + | is actually <b>not</b> a sum - at least not in the same sense as a finite sum. For example, consider | |

| − | <math> | + | <math>1 - 1 + 1 - 1 + 1 - ...</math>, |

| − | <math> | + | <math>5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + ...</math>, and |

| − | + | <math>1/3 + 2/9 + 4/27 + 8/81 + ...</math> | |

| − | + | There is no way to say what either of the first two "sums" are equal to in the conventional sense, because as you keep adding values, the total sum changes. The first sum keeps going between 1 and 0, and the second gets as large as we wish. The third one, however, as you keep adding values, it gets closer and closer to a specific number. This is the kind of thing we want to think of when considering these types of sums. As you add more and more terms, the total sum gets as close as we'd like to 1 (we'll prove this soon). So we say that | |

| − | <math> | + | <math>1/3 + 2/9 + 4/27 + 8/81 + ... = 1</math> |

| − | < | + | One must be careful here, because you can never add enough terms to actually reach 1. This statement is just <i>notation</i> for the fact that if we keep adding values, we can get as close as we'd like to 1. Another way of stating this is as follows: |

| − | + | Let <math>a_1, a_2, a_3, ...</math> be some sequence of values, and define <math>S_n = a_1 + a_2 + ... + a_n</math>. Then if <math>lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} S_n</math> exists and is equal to <math>L</math>, then we say | |

| − | <math> | + | <math>a_1 + a_2 + a_3 + ... = L</math>. |

| − | + | Otherwise, we say that the sum doesn't converge. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | == | + | ==Proof== |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | There's a few different proofs I can think of for this fact, but there is one in particular which requires no extra "machinery", and is very convincing. First, define <math>S_n</math> to be the nth partial sum, i.e. the sum of the first n terms. | |

| − | + | <math>S_n=1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^n</math> | |

| − | + | Then we can use a little trick to obtain a closed form expression for this sum: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math>S_n - rS_n = (1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^n) - r(1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^n)</math> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math>S_n(1-r) = 1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^n - (r+r^2+r^3+\cdots+r^{n+1})</math> | |

| − | + | Then we see that <math>r</math> and <math>-r</math> cancel, <math>r^2</math> and <math>-r^2</math> cancel, all the way up to <math>r^n</math> and <math>-r^n</math>, leaving only | |

| − | ---- | + | <math>S_n(1-r) = 1-r^{n+1} = \frac{1-r^{n+1}}{1-r}</math> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math>S_n = \frac{1}{1-r} - \frac{r^{n+1}}{1-r}</math> | |

| − | + | So then, if <math>|r|<1</math>, it's not terribly hard to see that | |

| − | + | <math>lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} S_n = \frac{1}{1-r}</math> | |

| − | + | This is great! This isn't quite the formula I listed above, but | |

| − | + | <math>aS_n = a+ar+ar^2+\cdots+ar^n</math> | |

| − | + | and | |

| − | --- | + | <math>lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} aS_n |

| − | = | + | = lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} a \left(\frac{1}{1-r} - \frac{r^{n+1}}{1-r}\right) |

| + | = \frac{a}{1-r}</math> | ||

| − | + | So this is the result we were looking for. | |

| − | + | ---- | |

| − | + | ==Substitution== | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Looking at our proof, if we replace <math>r</math> with <math>f(x)</math>, it's exactly the same, and you get that | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math>S_n = 1 + f(x) + f(x)^2 + \cdots + f(x)^n = \frac{1}{1-f(x)} - \frac{f(x)^{n+1}}{1-f(x)}</math> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | and thus, for <math>|f(x)|<1</math>, the formula we like still holds: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math>a + af(x) + af(x)^2 + \cdots = \frac{a}{1-f(x)}</math> | |

| − | + | ---- | |

| + | ==Examples== | ||

| − | + | '''Example 1''' | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Imagine John has a giant house-sized block of cheese he intends to share with the entire world. First he cuts the cheese in half and gives one half to his mom. He then cuts what's left in half and gives one piece to a friend. He continues this process indefinitely. In the limit, how much cheese will he have given away? Will he ever lose all of his cheese? | |

| − | + | Both of these questions can be answered through intuition of situation alone, but we will formulate the question in terms of a geometric series. After n steps, the fraction of his cheese John will have given away is | |

| − | + | <math>S_n \;=\; \frac{1}{2} \,+\, \frac{1}{4} \,+\, \frac{1}{8} \,+\, \frac{1}{16} \,+\, \cdots \,+\, \frac{1}{2^n}</math> | |

| − | + | because first he gives away half, then half of the half he has left (one fourth), etc. This is a geometric progression with common factor 1/2, and we need only apply the formula we just spend all that time talking about | |

| − | + | <math>\frac{1}{2} \,+\, \frac{1}{4} \,+\, \frac{1}{8} \,+\, \frac{1}{16} \,+\, \cdots = \frac{ 1/2 }{ 1 - 1/2 } = 1 </math> | |

| − | < | + | Thus in the limit, he will have given away his entire cheese block. But as discussed above, if he is always allowed to cut his remaining cheese in half, he will <b>always</b> have cheese. If his cheese is made up of indivisible cheese molecules, he will eventually have to give away his last molecule of cheese. |

| − | + | '''Example 2''' | |

| − | + | Let's look at an example from optics. Consider light incident on a glass sheet: | |

| − | + | [[Image:Reflect.png]] | |

| − | <math> | + | Some portion of the incident light is reflected from the surface and some portion is transmitted into the glass. Some of this transmitted light then reflects off the lower surface of the glass. Then some of this is transmitted through to contribute to the intensity of the reflection. Let's say that when light impinges on a surface like this, <math>rL</math> of the light is reflected and <math>tL</math> is transmitted through the surface. We call <math>r</math> and <math>t</math> the reflectance and transmittance coefficients, respectively, and <math>L</math> is how much light there was to begin with. We can think of L as an intensity. |

| − | + | Then in the image above, the total intensity of the reflection is <math>rL + trtL</math> (accounting for both reflections). But there is also a part of the second ray which is reflected back into the sheet. This continues ad infinitum: | |

| − | + | [[Image:Super-reflect.png]] | |

| − | + | So, if you account carefully for the reflections, the total intensity of the reflection is | |

| − | <math> | + | <math>L_{tot} = rL + trtL + trrrtL + trrrrrtL + \cdots</math> |

| − | + | Notice that this is a geometric progression, starting with <math>trtL</math>, so | |

| − | <math> | + | <math>L_{tot} = rL + \frac{trtL}{1-rr} = rL + \frac{rt^2L}{1-r^2}</math> |

| − | + | ---- | |

| − | + | ==Exercises, for some practice== | |

| − | + | '''Exercise 1''' | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math>\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^3 \,+\, \left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^4 \,+\, \left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^5 \,+\, \left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^6 \,+\, \cdots</math> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | '''Exercise 2''' | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math> \sum_{n=0}^\infty \left( \frac{2^{n+1}}{5^n} \right) </math> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | '''Exercise 3''' | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <math> \sum_{n=1}^\infty \left(-1\right)^n \frac{3}{4^n} </math> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | '''Exercise 4''' | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | </ | + | <math> 1 + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} + \frac{1}{2} + \cdots </math> |

---- | ---- | ||

| Line 204: | Line 157: | ||

<div style="font-family: Verdana, sans-serif; font-size: 14px; text-align: justify; width: 70%; margin: auto; border: 1px solid #aaa; padding: 2em;"> | <div style="font-family: Verdana, sans-serif; font-size: 14px; text-align: justify; width: 70%; margin: auto; border: 1px solid #aaa; padding: 2em;"> | ||

| − | The Spring 2013 Math Squad 2013 was supported by an anonymous [ | + | The Spring 2013 Math Squad 2013 was supported by an anonymous [https://www.projectrhea.org/learning/donate.php gift] to [https://www.projectrhea.org/learning/about_Rhea.php Project Rhea]. If you enjoyed reading these tutorials, please help Rhea "help students learn" with a [https://www.projectrhea.org/learning/donate.php donation] to this project. Your [https://www.projectrhea.org/learning/donate.php contribution] is greatly appreciated. |

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 12:06, 25 November 2013

Contents

Geometric Series

by Alec McGail, proud Member of the Math Squad.

INTRODUCTION A geometric series is a very useful infinite sum which seems to pop up everywhere:

If $ |r|<1 $,

$ a+ar+ar^2+ar^3+ar^4+\cdots=\frac{a}{1-r} $.

In this tutorial, I will explain exactly what this formula means, why it's true, and how to use it.

Explanation

If you fully understand what the above statement means, you may skip this section. If you've ever worked with infinite sums, you probably have some idea of what the "$ \cdots $" is trying to imply. It's important, however, to know that mathematically, the expression

$ a_1 + a_2 + a_3 + \cdots $

is actually not a sum - at least not in the same sense as a finite sum. For example, consider

$ 1 - 1 + 1 - 1 + 1 - ... $,

$ 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + ... $, and

$ 1/3 + 2/9 + 4/27 + 8/81 + ... $

There is no way to say what either of the first two "sums" are equal to in the conventional sense, because as you keep adding values, the total sum changes. The first sum keeps going between 1 and 0, and the second gets as large as we wish. The third one, however, as you keep adding values, it gets closer and closer to a specific number. This is the kind of thing we want to think of when considering these types of sums. As you add more and more terms, the total sum gets as close as we'd like to 1 (we'll prove this soon). So we say that

$ 1/3 + 2/9 + 4/27 + 8/81 + ... = 1 $

One must be careful here, because you can never add enough terms to actually reach 1. This statement is just notation for the fact that if we keep adding values, we can get as close as we'd like to 1. Another way of stating this is as follows:

Let $ a_1, a_2, a_3, ... $ be some sequence of values, and define $ S_n = a_1 + a_2 + ... + a_n $. Then if $ lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} S_n $ exists and is equal to $ L $, then we say

$ a_1 + a_2 + a_3 + ... = L $.

Otherwise, we say that the sum doesn't converge.

Proof

There's a few different proofs I can think of for this fact, but there is one in particular which requires no extra "machinery", and is very convincing. First, define $ S_n $ to be the nth partial sum, i.e. the sum of the first n terms.

$ S_n=1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^n $

Then we can use a little trick to obtain a closed form expression for this sum:

$ S_n - rS_n = (1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^n) - r(1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^n) $

$ S_n(1-r) = 1+r+r^2+\cdots+r^n - (r+r^2+r^3+\cdots+r^{n+1}) $

Then we see that $ r $ and $ -r $ cancel, $ r^2 $ and $ -r^2 $ cancel, all the way up to $ r^n $ and $ -r^n $, leaving only

$ S_n(1-r) = 1-r^{n+1} = \frac{1-r^{n+1}}{1-r} $

$ S_n = \frac{1}{1-r} - \frac{r^{n+1}}{1-r} $

So then, if $ |r|<1 $, it's not terribly hard to see that

$ lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} S_n = \frac{1}{1-r} $

This is great! This isn't quite the formula I listed above, but

$ aS_n = a+ar+ar^2+\cdots+ar^n $

and

$ lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} aS_n = lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} a \left(\frac{1}{1-r} - \frac{r^{n+1}}{1-r}\right) = \frac{a}{1-r} $

So this is the result we were looking for.

Substitution

Looking at our proof, if we replace $ r $ with $ f(x) $, it's exactly the same, and you get that

$ S_n = 1 + f(x) + f(x)^2 + \cdots + f(x)^n = \frac{1}{1-f(x)} - \frac{f(x)^{n+1}}{1-f(x)} $

and thus, for $ |f(x)|<1 $, the formula we like still holds:

$ a + af(x) + af(x)^2 + \cdots = \frac{a}{1-f(x)} $

Examples

Example 1

Imagine John has a giant house-sized block of cheese he intends to share with the entire world. First he cuts the cheese in half and gives one half to his mom. He then cuts what's left in half and gives one piece to a friend. He continues this process indefinitely. In the limit, how much cheese will he have given away? Will he ever lose all of his cheese?

Both of these questions can be answered through intuition of situation alone, but we will formulate the question in terms of a geometric series. After n steps, the fraction of his cheese John will have given away is

$ S_n \;=\; \frac{1}{2} \,+\, \frac{1}{4} \,+\, \frac{1}{8} \,+\, \frac{1}{16} \,+\, \cdots \,+\, \frac{1}{2^n} $

because first he gives away half, then half of the half he has left (one fourth), etc. This is a geometric progression with common factor 1/2, and we need only apply the formula we just spend all that time talking about

$ \frac{1}{2} \,+\, \frac{1}{4} \,+\, \frac{1}{8} \,+\, \frac{1}{16} \,+\, \cdots = \frac{ 1/2 }{ 1 - 1/2 } = 1 $

Thus in the limit, he will have given away his entire cheese block. But as discussed above, if he is always allowed to cut his remaining cheese in half, he will always have cheese. If his cheese is made up of indivisible cheese molecules, he will eventually have to give away his last molecule of cheese.

Example 2

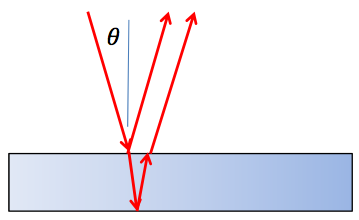

Let's look at an example from optics. Consider light incident on a glass sheet:

Some portion of the incident light is reflected from the surface and some portion is transmitted into the glass. Some of this transmitted light then reflects off the lower surface of the glass. Then some of this is transmitted through to contribute to the intensity of the reflection. Let's say that when light impinges on a surface like this, $ rL $ of the light is reflected and $ tL $ is transmitted through the surface. We call $ r $ and $ t $ the reflectance and transmittance coefficients, respectively, and $ L $ is how much light there was to begin with. We can think of L as an intensity.

Then in the image above, the total intensity of the reflection is $ rL + trtL $ (accounting for both reflections). But there is also a part of the second ray which is reflected back into the sheet. This continues ad infinitum:

So, if you account carefully for the reflections, the total intensity of the reflection is

$ L_{tot} = rL + trtL + trrrtL + trrrrrtL + \cdots $

Notice that this is a geometric progression, starting with $ trtL $, so

$ L_{tot} = rL + \frac{trtL}{1-rr} = rL + \frac{rt^2L}{1-r^2} $

Exercises, for some practice

Exercise 1

$ \left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^3 \,+\, \left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^4 \,+\, \left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^5 \,+\, \left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^6 \,+\, \cdots $

Exercise 2

$ \sum_{n=0}^\infty \left( \frac{2^{n+1}}{5^n} \right) $

Exercise 3

$ \sum_{n=1}^\infty \left(-1\right)^n \frac{3}{4^n} $

Exercise 4

$ 1 + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} + \frac{1}{2} + \cdots $

Questions and comments

If you have any questions, comments, etc. please, please please post them below:

- Comment / question 1

- Comment / question 2

The Spring 2013 Math Squad 2013 was supported by an anonymous gift to Project Rhea. If you enjoyed reading these tutorials, please help Rhea "help students learn" with a donation to this project. Your contribution is greatly appreciated.