| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

[[File:Bayes derivation.png|500px|thumbnail]] | [[File:Bayes derivation.png|500px|thumbnail]] | ||

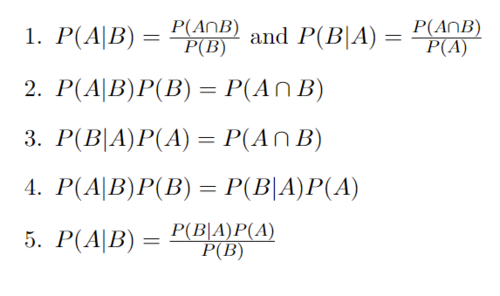

Looking at step 1 with the definition of conditional probabilities, it is assumed that P(A) and P(B) are not 0. | Looking at step 1 with the definition of conditional probabilities, it is assumed that P(A) and P(B) are not 0. | ||

| + | In step 2 we multiply both sides by P(B) and in step 3 we multiply both sides by P(A) and we end up with the same result on the right hand side of each. | ||

| + | In step 4 we are able to set both left sides equal to each other since they both have the same right hand side. | ||

| + | In step 5 we divide both sides by P(B) and we arrive at Baye's Theorem. | ||

Revision as of 10:41, 3 November 2022

Probability : Group 4

Kalpit Patel Rick Jiang Bowen Wang Kyle Arrowood

This is an edit

Probability, Conditional Probability, Bayes Theorem Disease example

Definition: Probability is a measure of the likelihood of an event to occur. Many events cannot be predicted with total certainty. We can predict only the chance of an event to occur i.e., how likely they are going to happen, using it. Probability can range from 0 to 1, where 0 means the event to be an impossible one and 1 indicates a certain event. The probability of all the events in a sample space adds up to 1.

Baye's Theorem Derivation: Starting with the definition of Conditional Probability

Looking at step 1 with the definition of conditional probabilities, it is assumed that P(A) and P(B) are not 0. In step 2 we multiply both sides by P(B) and in step 3 we multiply both sides by P(A) and we end up with the same result on the right hand side of each. In step 4 we are able to set both left sides equal to each other since they both have the same right hand side. In step 5 we divide both sides by P(B) and we arrive at Baye's Theorem.