| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | G.H. Hardy, as I view him upon reading his words, was a fluent writer; his sentences are meaningful and his books is not effectively read with the purpose of leisure. When met in person, I have little doubt that he will render himself as rude and arrogant and pathetic to me and the many who will misunderstand him and many significant ideas. He is honest, neither haughty nor humble, and he speaks of his word without any discretion or regret, all the time knowing that he will be disliked but nevertheless not caring since those who take offense are not too worthy of talking with anyway. For instance, he dismisses exposition, criticism, appreciation as work of "second-rate mind" (which, ironically but deliberately, includes himself who is writing about his view on mathematics) and suggests thta "most people can do nothing at all well... perhaps five or even ten percent of men can do something rather well." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Is his not his mathematics that impresses me, and I apologize Hardy for not understanding his work and appreciating him for that. He is frank with himself and his thoughts. He regards his study highly, and justly so, but never despise for other subjects lest the people who represents them are idiots. It is the expression of the limit of human capacity, be it in mathematics or cricket, that is worth our time. And it is with selfishness that a "good work" is done, not with a humble mind. I find it interesting, that I find many ideas echoing his own, particularly of ideas I found in the Fountainhead by Ayn Rand. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I used to be rather lost by when I was rather certain that I did not have ingenious mind to be a great mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, poet, or a writer, professions which I most admire.. Here is what Hardy says on that note: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''"Their answers [to the justification to their existence] will usually take one or other of two forms... 1) 'I do what I do because it is the one and only thing that I can do at all well. I am a lawyer, or a stockbroker, or a professional cricketer, because I have some real talent for that particular job. I am a lawyer because I have a fluent tongue, and am interested in legal subtleties; I am a stockbroker because my judgement of the markets is quick and sound; I am professional cricketer because I can bat unusually well. I agree that it might be better to be a poet or a mathematician, but unfortunately, I have no talent for such pursuits.'... he would be silly if he surrendered any decent opportunity of exercising his one talent in order to do undistinguished work in other field.'' | ||

Revision as of 18:32, 11 October 2011

Brief Biography and Reflection

Upon finishing A Mathematician's Apology by G.H. Hardy, I found the man and his attitude of the profession of mathematics to be notable. I recommend the book, and I plan to revisit the book again in a year or so.

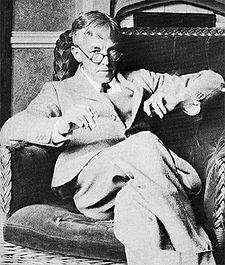

Godfrey Harold 'G.H.' Hardy, born 7 Feb 1877, was an English Mathematician with significant contributions made to pure mathematics. Born between highly intelligent and wealthy parents, Hardy was "prodigiously clever", and unfortunately, he was aware of his brilliance well. Top of his class, sweeper of academic prizes, scholarships, Hardy went on to Winchester College to study mathematics, place he disliked except for the mathematical education he received. In tradition with eccentric character of many great mathematicians, he was socially awkward and shy and could not bear to look at himself at the mirror.

Despite his disinclination towards meeting new people, Hardy was an honest man and seems to communicate with brutal honesty. His most notable mathematical achievements were in collaboration with his colleagues, two notable being English Mathematician J.E. Littlewood and Indian Mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan. When asked of his greatest achievement in the field of mathematics by Paul Erdős, he replied that it was the discovery of Srinivasa Ramanujan, who's display of brilliance awed Hardy and prompted him to bring Ramanujan to England to collaborate with him.

Hardy was a pure mathematician who wished that his work would never be applied, to be completely pure within the realm of mathematical world he believed existed independent of the physical world.

He would have loathed having been subject of biography by a non-mathematician who does cannot share his appreciation for mathematics and cannot understand his mathematical achievements. Therefore, I leave with his own line in justifying his life:

"I have never done anything 'useful'. No discovery of mine has made, or is likely to make, directly or indirectly, for good or ill, the least difference to the amenity of the world... The case for my life, then, or for that of nay one else who has been a mathematician in the same sense in which I have been on, is this: that I have added something to knowledge and helped others to add more; and that theses somethings have a value which differs in degree only, and not in kind, from that of the creations of the great mathematicians or of any of the other artists, great or small, who have left some kind of memorial behind them."

G.H. Hardy, as I view him upon reading his words, was a fluent writer; his sentences are meaningful and his books is not effectively read with the purpose of leisure. When met in person, I have little doubt that he will render himself as rude and arrogant and pathetic to me and the many who will misunderstand him and many significant ideas. He is honest, neither haughty nor humble, and he speaks of his word without any discretion or regret, all the time knowing that he will be disliked but nevertheless not caring since those who take offense are not too worthy of talking with anyway. For instance, he dismisses exposition, criticism, appreciation as work of "second-rate mind" (which, ironically but deliberately, includes himself who is writing about his view on mathematics) and suggests thta "most people can do nothing at all well... perhaps five or even ten percent of men can do something rather well."

Is his not his mathematics that impresses me, and I apologize Hardy for not understanding his work and appreciating him for that. He is frank with himself and his thoughts. He regards his study highly, and justly so, but never despise for other subjects lest the people who represents them are idiots. It is the expression of the limit of human capacity, be it in mathematics or cricket, that is worth our time. And it is with selfishness that a "good work" is done, not with a humble mind. I find it interesting, that I find many ideas echoing his own, particularly of ideas I found in the Fountainhead by Ayn Rand.

I used to be rather lost by when I was rather certain that I did not have ingenious mind to be a great mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, poet, or a writer, professions which I most admire.. Here is what Hardy says on that note:

"Their answers [to the justification to their existence] will usually take one or other of two forms... 1) 'I do what I do because it is the one and only thing that I can do at all well. I am a lawyer, or a stockbroker, or a professional cricketer, because I have some real talent for that particular job. I am a lawyer because I have a fluent tongue, and am interested in legal subtleties; I am a stockbroker because my judgement of the markets is quick and sound; I am professional cricketer because I can bat unusually well. I agree that it might be better to be a poet or a mathematician, but unfortunately, I have no talent for such pursuits.'... he would be silly if he surrendered any decent opportunity of exercising his one talent in order to do undistinguished work in other field.