(New page: ='''2.1 Converge'''= Definition. Converge A sequence of numbers <math>x_{1},x_{2},\cdots,x_{n},\cdots</math> is said to converge to a limit <math>x</math> if, for every <math>\epsilon>...) |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | ='''2.1 Converge'''= | + | = '''2.1 Converge''' = |

| − | Definition. Converge | + | Definition. Converge |

| − | A sequence of numbers < | + | A sequence of numbers <span class="texhtml">''x''<sub>1</sub>,''x''<sub>2</sub>,⋅⋅⋅,''x''<sub>''n''</sub>,⋅⋅⋅</span> is said to converge to a limit <span class="texhtml">''x''</span> if, for every <span class="texhtml">ε > 0</span> , there exists a number <math class="inline">n_{\epsilon}\in\mathbf{N}</math> such that |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | + | <math class="inline">\left|x_{n}-x\right|<\epsilon,\;\forall n\geq n_{\epsilon}</math>. | |

| − | + | "<span class="texhtml">''x''<sub>''n''</sub>→''x'' as ''n''→∞</span>". | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | + | Given a random sequence <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{1}\left(\omega\right),\mathbf{X}_{2}\left(\omega\right),\cdots,\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right),\cdots</math> for any particular <span class="texhtml">ω<sub>0</sub>∈''S''</span> , we have <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{1}\left(\omega_{0}\right),\mathbf{X}_{2}\left(\omega_{0}\right),\cdots,\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega_{0}\right)</math> is a sequence of real numbers. | |

| − | + | • It may converge to a number <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}\left(\omega_{0}\right)</math> that may be a function of <span class="texhtml">ω<sub>0</sub></span> . | |

| − | • | + | • It may not converge. |

| − | + | Most likely, <math class="inline">\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\}</math> converge for some <span class="texhtml">ω∈''S''</span> and will diverge for other <span class="texhtml">ω∈''S''</span> . When we study stochastic convergence, we study the set <span class="texhtml">''A''⊂''S''</span> for which <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{1}\left(\omega\right),\mathbf{X}_{2}\left(\omega\right),\cdots,\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right),\cdots</math> is a convergent sequence of real numbers. | |

| − | 2.1. | + | '''2.1.1 Definition. Converge everywhere''' |

| − | + | We say a sequence of random variables converges everywhere (e) if the sequence <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{1}\left(\omega\right),\mathbf{X}_{2}\left(\omega\right),\cdots,\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right),\cdots</math> each converge to a number <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}\left(\omega\right)</math> for each <math class="inline">\omega\in\mathcal{S}</math> . | |

| − | + | Note | |

| − | + | • The number <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}\left(\omega\right)</math> that <math class="inline">\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\}</math> converges to is in general a function of <span class="texhtml">ω</span> . | |

| − | + | • Convergence (e) is too strong to be useful. | |

| − | + | 2.1.2 Definition. Converge almost everywhere | |

| − | + | A random sequence <math class="inline">\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\}</math> converges almost everywhere (a.e.) if the set of outcomes <math class="inline">A\subset\mathcal{S}</math> such that <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\rightarrow\mathbf{X}\left(\omega\right),\;\omega\in A</math> exists and has probability 1: <math class="inline">P\left(A\right)=1</math> . Other names for this are: almost surely (a.s.) and convergence with probability one. We write this as “<math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow(a.e)\rightarrow\mathbf{X}</math> ” or “<math class="inline">P\left(\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow\mathbf{X}\right\} \right)=1.</math> ” | |

| − | + | 2.1.3 Definition. Converge in mean-square | |

| − | + | We say that a random sequence converges in mean-square (m.s.) to a random variable <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}</math> if <math class="inline">E\left[\left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right|^{2}\right]\rightarrow0\textrm{ as }n\rightarrow\infty</math>. | |

| − | + | '''Note''' | |

| + | Convergence (m.s.) is also called “limit in the mean convergence” and is written “l.i.m. <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{n}=\mathbf{X}</math> ” (bad). Better notation is <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow(m.s.)\rightarrow\mathbf{X}</math> . | ||

| − | + | 2.1.4 Definition. Converge in probability | |

| − | + | A random sequence <math class="inline">\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\}</math> converges in probability (p) to a random variable <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}</math> if, <math class="inline">\forall\epsilon > 0 P\left(\left\{ \left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right|>\epsilon\right\} \right)\rightarrow0</math> as <math class="inline">n\rightarrow\infty</math>. | |

| + | As opposed to <math class="inline">P\left(\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow(a.e.)\rightarrow\mathbf{X}\right\} \right)</math> . Convergence (a.e.) is a much stronger form of convergence. | ||

| − | 2.1. | + | 2.1.5 Definition. Converge in distribution |

| − | A random sequence \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\} | + | A random sequence <math class="inline">\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\}</math> converges in distribution (d) to a random variable <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}</math> if <math class="inline">F_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)\rightarrow F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)</math> at every point <math class="inline">x\in\mathbf{R}</math> where <math class="inline">F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)</math> is continuous. |

| − | + | Example: Central Limit Theorem | |

| − | + | 2.1.6 Definition. Converge in density | |

| − | + | A random sequence <math class="inline">\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\}</math> converges in density (density) to a random variable <math class="inline">\mathbf{X} if f_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)\rightarrow f_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)\textrm{ as }n\rightarrow\infty</math> for every <math class="inline">x\in\mathbf{R}</math> where <math class="inline">F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)</math> is continuous. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | 2.1.7 Convergence in distribution vs. convergence in density | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | • | + | • Aren't convergence in density and distribution equivalent? NO! |

| − | • | + | • Example: Let <math class="inline">\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\}</math> be a sequence of random variables with <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{n}</math> having pdf <math class="inline">f_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)=\left[1+\cos\left(2\pi nx\right)\right]\cdot\mathbf{1}_{\left[0,1\right]}\left(x\right)</math>. <math class="inline">f_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)</math> is a valid pdf for <math class="inline">n=1,2,3,\cdots</math>. The cdf of <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{n}</math> is <math class="inline">F_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)=\left\{ \begin{array}{lll} 0 , x<0\\ x+\frac{1}{2\pi n}\sin\left(x2\pi n\right) , x\in\left[0,1\right]\\ 1 , x>1. \end{array}\right.</math> |

| − | • | + | • Now define <math class="inline">F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)=\left\{ \begin{array}{lll} 0 , x<0\\ x , x\in\left[0,1\right]\\ 1 , x>;1. \end{array}\right. </math> |

| − | • \ | + | • Because <math class="inline">F_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)\rightarrow F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)</math> as <math class="inline">n\rightarrow\infty ,\therefore\mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow\left(d\right)\rightarrow\mathbf{X}</math>. |

| − | + | • The pdf of <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}</math> corresponding to <math class="inline">F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)</math> is <math class="inline">f_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)=\mathbf{1}_{\left[0,1\right]}\left(x\right)</math>. | |

| − | + | • What does <math class="inline">f_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)</math> look like? We do not have convergence in density. | |

| − | + | • <math class="inline">\therefore</math> Convergence in density and convergence in distribution are NOT equivalent. In fact, convergence (density) <math class="inline">\left(\nLeftarrow\right)\Longrightarrow</math> convergence (distribution) | |

| − | + | 2.1.8 Cauchy criterion for convergence | |

| − | Note | + | Recall that a sequence of numbers <math class="inline">x_{1},x_{2},\cdots,x_{n}</math> converges to <math class="inline">x</math> if <math class="inline">\forall\epsilon>0 , \exists n_{\epsilon}\in\mathbf{N}</math> such that <math class="inline">\left|x_{n}-x\right|<\epsilon,\;\forall n\geq n_{\epsilon}</math>. To use this definition, you must know <math class="inline">x</math> . The Cauchy criterion gives us a way to test for convergence without knowing the limit <math class="inline">x</math> . |

| + | |||

| + | Cauchy criterion | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math class="inline">\left\{ x_{n}\right\}</math> is a sequence of real numbers and <math class="inline">\left|x_{n+m}-x_{n}\right|\rightarrow0</math> as <math class="inline">n\rightarrow\infty</math> for all <math class="inline">m\in\mathbf{N}</math> , then <math class="inline">\left\{ x_{n}\right\}</math> converges to a real number. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note | ||

The Cauchy criterion can be applied to various forms of stochastic convergence. We look at: | The Cauchy criterion can be applied to various forms of stochastic convergence. We look at: | ||

| − | \mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow\mathbf{X} | + | <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow\mathbf{X}</math> (original) |

| + | |||

| + | <math class="inline">\mathbf{X}_{n} and \mathbf{X}_{n+m}</math> (Cauchy criterion) | ||

| + | |||

| + | e.g. | ||

| − | \mathbf{X}_{n} | + | If <math class="inline">\varphi\left(n,m\right)=E\left[\left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}_{n+m}\right|^{2}\right]\rightarrow0</math> as <math class="inline">n\rightarrow\infty</math> for all <math class="inline">m=1,2,\cdots</math> , then <math class="inline">\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\right\}</math> converges in mean-square. |

| − | + | 2.1.9 Comparison of modes of convergence | |

| + | <br> | ||

| − | + | [[Image:pasted37.png]] | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| + | convergence <math class="inline">\left(m.s.\right) \Longrightarrow</math> convergence <math class="inline">\left(p\right)</math> | ||

| + | <math class="inline">p\left(\left\{ \left|\mathbf{X}-\mu\right|>\epsilon\right\} \right)\leq\frac{E\left[\left(\mathbf{X}-\mu\right)^{2}\right]}{\epsilon^{2}}=\frac{\sigma_{\mathbf{X}}^{2}}{\epsilon^{2}}</math> | ||

| − | + | <math class="inline">\Longrightarrow p\left(\left\{ \left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right|>\epsilon\right\} \right)\leq\frac{E\left[\left(\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right)^{2}\right]}{\epsilon^{2}}.</math> | |

| − | + | Thus, <math class="inline">m.s.</math> convergence <math class="inline">\Longrightarrow E\left[\left(\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right)^{2}\right]\rightarrow0</math> as <math class="inline">n\rightarrow\infty \Longrightarrow p\left(\left\{ \left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right|>\epsilon\right\} \right)\rightarrow0</math> as <math class="inline">n\rightarrow\infty</math> . | |

| − | + | convergence <math class="inline">\left(a.e.\right) \Longrightarrow</math> convergence <math class="inline">\left(p\right)</math> | |

| − | + | Follows from definitions, converse is not true. | |

| − | convergence \left(a.e.\right) | + | convergence <math class="inline">\left(d\right)</math> is “weaker than” convergence <math class="inline">\left(a.e.\right)</math> , <math class="inline">\left(m.s.\right)</math> , or <math class="inline">\left(p\right)</math> . |

| − | + | <math class="inline">\left(a.e.\right)\Rightarrow\left(d\right) , \left(m.s.\right)\Rightarrow\left(d\right)</math> , and <math class="inline">\left(p\right)\Rightarrow\left(d\right)</math> . | |

| − | + | Note | |

| − | \left(a.e.\right)\ | + | <math class="inline">\left(a.e.\right)\nRightarrow\left(m.s.\right)</math> and <math class="inline">\left(m.s.\right)\nRightarrow\left(a.e.\right)</math> . |

| − | Note | + | Note |

| − | + | The Chebyshev inequality is a valuable tool for working with <math class="inline">m.s.</math> convergence. | |

| − | + | ---- | |

| + | [[ECE600|Back to ECE600]] | ||

| − | + | [[ECE 600 Sequences of Random Variables|Back to Sequences of Random Variables]] | |

Latest revision as of 10:37, 30 November 2010

2.1 Converge

Definition. Converge

A sequence of numbers x1,x2,⋅⋅⋅,xn,⋅⋅⋅ is said to converge to a limit x if, for every ε > 0 , there exists a number $ n_{\epsilon}\in\mathbf{N} $ such that

$ \left|x_{n}-x\right|<\epsilon,\;\forall n\geq n_{\epsilon} $.

"xn→x as n→∞".

Given a random sequence $ \mathbf{X}_{1}\left(\omega\right),\mathbf{X}_{2}\left(\omega\right),\cdots,\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right),\cdots $ for any particular ω0∈S , we have $ \mathbf{X}_{1}\left(\omega_{0}\right),\mathbf{X}_{2}\left(\omega_{0}\right),\cdots,\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega_{0}\right) $ is a sequence of real numbers.

• It may converge to a number $ \mathbf{X}\left(\omega_{0}\right) $ that may be a function of ω0 .

• It may not converge.

Most likely, $ \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\} $ converge for some ω∈S and will diverge for other ω∈S . When we study stochastic convergence, we study the set A⊂S for which $ \mathbf{X}_{1}\left(\omega\right),\mathbf{X}_{2}\left(\omega\right),\cdots,\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right),\cdots $ is a convergent sequence of real numbers.

2.1.1 Definition. Converge everywhere

We say a sequence of random variables converges everywhere (e) if the sequence $ \mathbf{X}_{1}\left(\omega\right),\mathbf{X}_{2}\left(\omega\right),\cdots,\mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right),\cdots $ each converge to a number $ \mathbf{X}\left(\omega\right) $ for each $ \omega\in\mathcal{S} $ .

Note

• The number $ \mathbf{X}\left(\omega\right) $ that $ \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\} $ converges to is in general a function of ω .

• Convergence (e) is too strong to be useful.

2.1.2 Definition. Converge almost everywhere

A random sequence $ \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\} $ converges almost everywhere (a.e.) if the set of outcomes $ A\subset\mathcal{S} $ such that $ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\rightarrow\mathbf{X}\left(\omega\right),\;\omega\in A $ exists and has probability 1: $ P\left(A\right)=1 $ . Other names for this are: almost surely (a.s.) and convergence with probability one. We write this as “$ \mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow(a.e)\rightarrow\mathbf{X} $ ” or “$ P\left(\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow\mathbf{X}\right\} \right)=1. $ ”

2.1.3 Definition. Converge in mean-square

We say that a random sequence converges in mean-square (m.s.) to a random variable $ \mathbf{X} $ if $ E\left[\left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right|^{2}\right]\rightarrow0\textrm{ as }n\rightarrow\infty $.

Note Convergence (m.s.) is also called “limit in the mean convergence” and is written “l.i.m. $ \mathbf{X}_{n}=\mathbf{X} $ ” (bad). Better notation is $ \mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow(m.s.)\rightarrow\mathbf{X} $ .

2.1.4 Definition. Converge in probability

A random sequence $ \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\} $ converges in probability (p) to a random variable $ \mathbf{X} $ if, $ \forall\epsilon > 0 P\left(\left\{ \left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right|>\epsilon\right\} \right)\rightarrow0 $ as $ n\rightarrow\infty $. As opposed to $ P\left(\left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow(a.e.)\rightarrow\mathbf{X}\right\} \right) $ . Convergence (a.e.) is a much stronger form of convergence.

2.1.5 Definition. Converge in distribution

A random sequence $ \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\} $ converges in distribution (d) to a random variable $ \mathbf{X} $ if $ F_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)\rightarrow F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right) $ at every point $ x\in\mathbf{R} $ where $ F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right) $ is continuous.

Example: Central Limit Theorem

2.1.6 Definition. Converge in density

A random sequence $ \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\} $ converges in density (density) to a random variable $ \mathbf{X} if f_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)\rightarrow f_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)\textrm{ as }n\rightarrow\infty $ for every $ x\in\mathbf{R} $ where $ F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right) $ is continuous.

2.1.7 Convergence in distribution vs. convergence in density

• Aren't convergence in density and distribution equivalent? NO!

• Example: Let $ \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\left(\omega\right)\right\} $ be a sequence of random variables with $ \mathbf{X}_{n} $ having pdf $ f_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)=\left[1+\cos\left(2\pi nx\right)\right]\cdot\mathbf{1}_{\left[0,1\right]}\left(x\right) $. $ f_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right) $ is a valid pdf for $ n=1,2,3,\cdots $. The cdf of $ \mathbf{X}_{n} $ is $ F_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)=\left\{ \begin{array}{lll} 0 , x<0\\ x+\frac{1}{2\pi n}\sin\left(x2\pi n\right) , x\in\left[0,1\right]\\ 1 , x>1. \end{array}\right. $

• Now define $ F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)=\left\{ \begin{array}{lll} 0 , x<0\\ x , x\in\left[0,1\right]\\ 1 , x>;1. \end{array}\right. $

• Because $ F_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right)\rightarrow F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right) $ as $ n\rightarrow\infty ,\therefore\mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow\left(d\right)\rightarrow\mathbf{X} $.

• The pdf of $ \mathbf{X} $ corresponding to $ F_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right) $ is $ f_{\mathbf{X}}\left(x\right)=\mathbf{1}_{\left[0,1\right]}\left(x\right) $.

• What does $ f_{\mathbf{X}_{n}}\left(x\right) $ look like? We do not have convergence in density.

• $ \therefore $ Convergence in density and convergence in distribution are NOT equivalent. In fact, convergence (density) $ \left(\nLeftarrow\right)\Longrightarrow $ convergence (distribution)

2.1.8 Cauchy criterion for convergence

Recall that a sequence of numbers $ x_{1},x_{2},\cdots,x_{n} $ converges to $ x $ if $ \forall\epsilon>0 , \exists n_{\epsilon}\in\mathbf{N} $ such that $ \left|x_{n}-x\right|<\epsilon,\;\forall n\geq n_{\epsilon} $. To use this definition, you must know $ x $ . The Cauchy criterion gives us a way to test for convergence without knowing the limit $ x $ .

Cauchy criterion

If $ \left\{ x_{n}\right\} $ is a sequence of real numbers and $ \left|x_{n+m}-x_{n}\right|\rightarrow0 $ as $ n\rightarrow\infty $ for all $ m\in\mathbf{N} $ , then $ \left\{ x_{n}\right\} $ converges to a real number.

Note

The Cauchy criterion can be applied to various forms of stochastic convergence. We look at:

$ \mathbf{X}_{n}\rightarrow\mathbf{X} $ (original)

$ \mathbf{X}_{n} and \mathbf{X}_{n+m} $ (Cauchy criterion)

e.g.

If $ \varphi\left(n,m\right)=E\left[\left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}_{n+m}\right|^{2}\right]\rightarrow0 $ as $ n\rightarrow\infty $ for all $ m=1,2,\cdots $ , then $ \left\{ \mathbf{X}_{n}\right\} $ converges in mean-square.

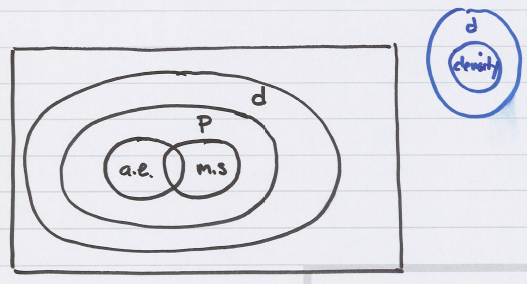

2.1.9 Comparison of modes of convergence

convergence $ \left(m.s.\right) \Longrightarrow $ convergence $ \left(p\right) $

$ p\left(\left\{ \left|\mathbf{X}-\mu\right|>\epsilon\right\} \right)\leq\frac{E\left[\left(\mathbf{X}-\mu\right)^{2}\right]}{\epsilon^{2}}=\frac{\sigma_{\mathbf{X}}^{2}}{\epsilon^{2}} $

$ \Longrightarrow p\left(\left\{ \left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right|>\epsilon\right\} \right)\leq\frac{E\left[\left(\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right)^{2}\right]}{\epsilon^{2}}. $

Thus, $ m.s. $ convergence $ \Longrightarrow E\left[\left(\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right)^{2}\right]\rightarrow0 $ as $ n\rightarrow\infty \Longrightarrow p\left(\left\{ \left|\mathbf{X}_{n}-\mathbf{X}\right|>\epsilon\right\} \right)\rightarrow0 $ as $ n\rightarrow\infty $ .

convergence $ \left(a.e.\right) \Longrightarrow $ convergence $ \left(p\right) $

Follows from definitions, converse is not true.

convergence $ \left(d\right) $ is “weaker than” convergence $ \left(a.e.\right) $ , $ \left(m.s.\right) $ , or $ \left(p\right) $ .

$ \left(a.e.\right)\Rightarrow\left(d\right) , \left(m.s.\right)\Rightarrow\left(d\right) $ , and $ \left(p\right)\Rightarrow\left(d\right) $ .

Note

$ \left(a.e.\right)\nRightarrow\left(m.s.\right) $ and $ \left(m.s.\right)\nRightarrow\left(a.e.\right) $ .

Note

The Chebyshev inequality is a valuable tool for working with $ m.s. $ convergence.