Jefferson vs Hamilton, the US begins

A team project for MA279, Fall 2013

History

Who is Jefferson?

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was born in Albemarle County, Virginia. Having inherited a considerable landed estate from his father and high social standing from his mother, Jefferson began building Monticello when he was twenty-six years old. Having attended the College of William and Mary, Jefferson practiced law and served in local government at a magistrate, county lieutenant, and member of the House of Burgess in his early professional life. [1] Jefferson was a Founding Father of the Untied States, draftsman of the U.S. Declaration of Independence; the nation’s first secretary of state (1789 – 1794), second vice president (1797 – 1801), and the third president (1801 – 1809). As public official, historian, philosopher, and plantation owner, he served his country for over five decades. [2]

Who is Hamilton?

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757 – July 12, 1804) was born in Charlestown, the capital of the island of Nevis, in the Leeward Islands. Hamilton’s father James abandoned Rachel, his wife, and their two sons. Rachel contracted a severe fever and died on February 19, 1768, leaving Hamilton effectively orphaned. Hamilton arrived in New York and enrolled in King’s college in 1773. In 1775, when the Revolutionary War began, Hamilton became part of the New York Provincial Artillery Company and fought in the battles of Long Islands, White Plains and Trenton. Hamilton was a Founding Father of the United States, chief of staff to General Washington, one of the most influential interpreters and promoters of the Constitution, the founder of the nation’s financial system, and the founder of the first American political party.[3]

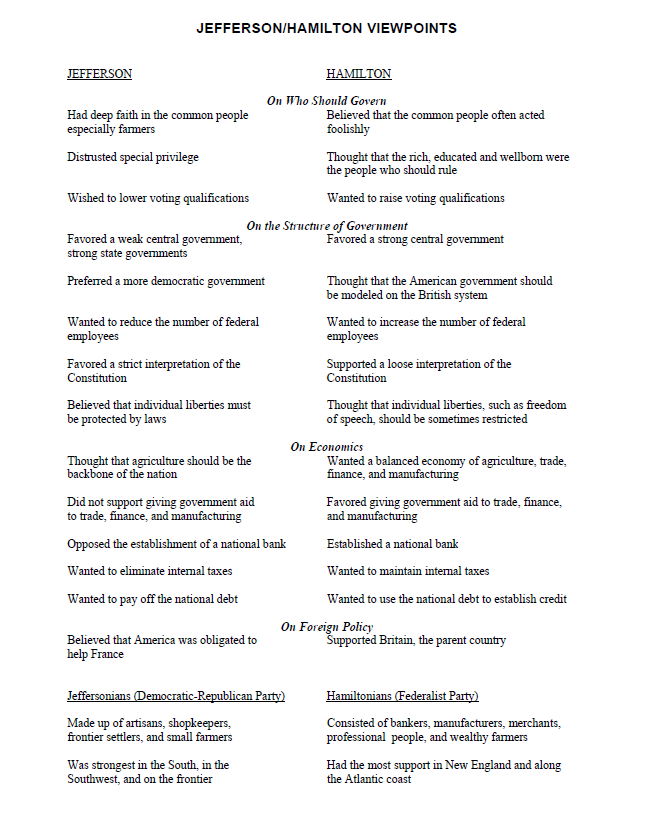

Jefferson v.s Hamilton Viewpoints [4]

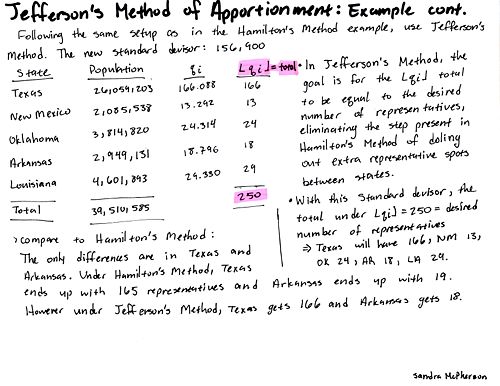

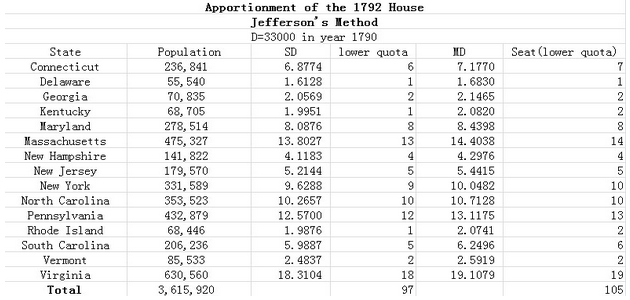

Jefferson’s Method

From 1790 to 1840, Jefferson’s Method for apportionment was used in the House of Representatives [5]. Around 1840, debate sprang up regarding the unfair advantage that large states seemed to have under Jefferson’s Method.

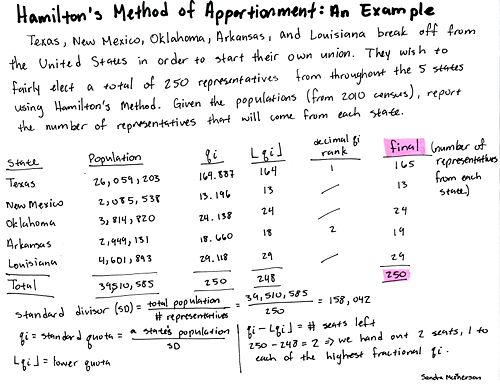

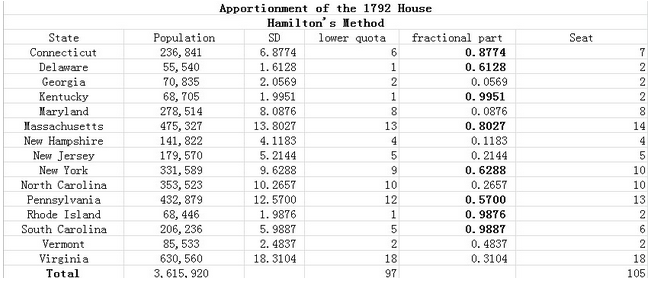

Hamilton’s Method

The apportionment method suggested by Alexander Hamilton was approved by Congress in 1791, but was subsequently vetoed by President Washington - in the very first exercise of the veto power by President of the United States. Hamilton's method was adopted by the US Congress in 1852 and was in use through 1911 when it was replaced by Webster’s method [6].

Data for population is obtained from the 2010 census. [7]

Math

Jefferson’s Method [9]

- Calculate the Standard Divisor which is the quotient of the total population and the number of seats.

- Calculate the Standard Quota for each state which is the quotient of a state’s population and the Standard Divisor.

- Assign each state its Lower Quota which is its Standard Quota rounded down.

- If the sum of Lower Quotas is equal to the number of seats, you’re done.

- Otherwise, find a Modified Divisor and respective Modified Quotas for which the sum of Modified Quotas is equal to the number of seats.

Example

Hamilton’s Method [9]

Calculate the Standard Divisor which is the quotient of the total population and the number of seats.

- Calculate the Standard Quota for each state which is the quotient of a state’s population and the Standard Divisor.

- Assign each state its Lower Quota which is its Standard Quota rounded down.

- If there are surplus seats, given them, one at a time, to states in descending order of the fractional parts of their Standard Quota.

Example

Rule violations

- Jefferson’s Method

- Upper quota violation: As you can see in the written example, Texas has an upper quota of 165 before changing the standard devisor, however it is awarded 166. This is an upper quota violation because a state should receive no more than their upper quota.

- Favors large states: Also from the written example, mathematically it is easier for Texas to jump up by 2, 164 to 166, than it is for the smaller states to increase by 1. This gives more power to larger states more often than giving power to small states.

- Hamilton’s Method

- No quota violation

- Alabama Paradox - An increase in the total number of seats to be apportioned causes a state to lose a seat.

- Population Paradox - An increase in a state’s population can cause it to lose a seat.

- New States Paradox - Adding a new state with its fair share of seats can affect the number of seats due other states.

- Favors large states

Sources:

[1] http://www.monticello.org/site/jefferson/thomas-jefferson-brief-biography

[2] http://www.biography.com/people/thomas-jefferson-9353715

[3] http://www.biography.com/people/alexander-hamilton-9326481

[4] http://www.palomar.edu/ehp/history/sgrenz/Study%20Guides/JEFFERSON-HAMILTON%20VIEWPOINTS.pdf

[5] http://www.ams.org/samplings/feature-column/fcarc-apportion2

[6] http://www.cut-the-knot.org/Curriculum/SocialScience/AHamilton.shtml

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._states_and_territories_by_population

[8] Tannenbaum, Peter. "The Mathematics of Apportionment." Trans. Array Excursions in Modern Mathematics. . 7th edition. Fresno, CA: Pearson Education, 2006. 122-151. Print.

[9] http://www.ctl.ua.edu/math103/apportionment/appmeth.htm

Feiyan Chen, Sandy McPherson, Christopher Michael Wendt, Wenjun Zhang