Contents

The plurality vote: must it lead to a 2-party system?

A team project for MA279, Fall 2013

Team members: Bennett Marsh, Edwin Baeza, Kenneth Brown, Amberlee Carl

Introduction

It is a well known phenomenon that plurality elections tend to support 2-party political systems. This observation is generally credited to sociologist Maurice Duverger, who studied it in the 1950s and 1960s. Though this idea is supported by many real-world examples, is it necessarily true that all plurality systems must lead to 2 dominant political parties? And if not, what are the other factors that could influence the development of the political party structure?

To answer these questions, we first answer the question of what one means by a "2-party system". For example, in the United States, most people would agree that there is currently a 2-party system, with the 2 dominant parties being the Republicans and Democrats. However, there do exist other parties, such as the Libertarian and Green parties. The standard definition is that a 2-party system is one in which nearly all of the elected officials belong to one of 2 parties, and these 2 parties control a large majority of the government's power. This is a fairly loose definition, but in most cases it is relatively clear whether or not a certain political system should be classified as a "2-party system".

Plurality Voting

Plurality voting systems are used to determine winners in elections based on single-member districts (i.e., candidates run for specific seats, and each seat may only have one winner). These come in two main varieties: the most popular, also known as "first-past-the-post", is used in most United States political elections. In this method, the candidate who receives more votes than any other candidate in a single round of voting is declared the winner (does not necessarily have to receive an absolute majority of votes). The other, known as "runoff" voting, consists of two separate rounds of voting. If one candidate has an absolute majority after the first round, he is declared the winner. Otherwise, the two candidates with the most votes compete head-to-head in a second round. In this way, the winner always receives an absolute majority.

Duverger's law applies to any type of plurality election. Plurality voting can be contrasted with other methods such as "proportional representation", in which the number of seats a certain party/group receives is proportional to the number of votes received (see below). Since candidates to not run for specific seats, these methods can help avoid the collapse into a two-party system, as there is more incentive for voters to vote for minor parties.

Duverger's Law

Duverger's Law, attributed by Maurice Duverger, states that in a system which a plurality vote takes place, with each voter getting a single vote for one candidate, and only a single candidate winning the election, a two-party system will emerge. There are two main reasons for this. They are tactical voting and fusion of minor parties. Tactical voting is when voters tend to change their vote from their top choice candidate to a vote for a stronger party so that their vote is not "wasted". For example, let us suppose that there are 100 voters: 40 prefer an extreme candidate, while the remaining 60 are split 40/20 between two moderate candidates, A and B, respectively. With each voter voting for their top choice, the extreme candidate will win. However, let's assume that the 20 moderate voters would prefer the other moderate candidate over the more extreme one. If these twenty switch their vote from B to A, A candidate wins. If not, the extreme candidate wins, and their vote was "wasted". This will ultimately lead to the collapse of the weaker moderate party, as voters desert this party in order to vote for one with a stronger chance of winning, and into a two-party system. Fusion of parties works similarly, where over time, two or more different parties will come together, combining and compromising between their ideals, in order to gain voters from both parties. As this new party developed, the parties coming together are abandoned, again leading to a two-party system.

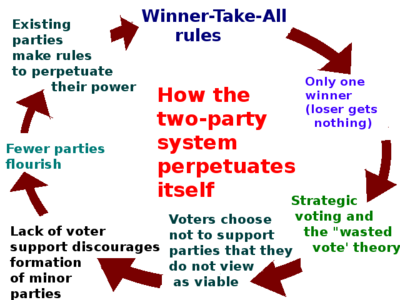

The below diagram illustrates how Plurality elections tend to promote 2-party systems (from wikipedia.org)

Examples of this can be seen all over the world. The United States is an excellent example. Over the course of history, the U.S. has been a two-party system, with a third party candidate very rarely winning an election. Germany and Spain are also good examples. While they have some legislative participation by small, minor parties, the majority of policymakers are from one of the two major parties in each respective country. Plurality voting leading to a two party system can also be seen in Malta and Australia.

Counterexamples

While it may seem that all plurality voting systems lead to 2-party, this is not always the case. The United Kingdom has had a stable 3-party system, consisting of the Liberal Democrats, the Conservative and Unionist Party, and the Labour Party, since 2005. Similarly, Canada has a 5-party system while India has a 38-party system, with each country’s respective parties being represented in their respective Parliament.

Converse

The converse of Duverger’s Law is not true. There are other systems that lead to 2-party systems. The country of Malta utilizes a single transferable voting system, in which a vote is transferred onto the remaining candidates based on voter preference and the proportion of excess votes. Single transferable voting is a proportional representation voting system intended to give minor parties a chance of winning, yet Malta has a 2-party political system. Australia is another example of a 2-party political system that arises from single transferable voting.

In countries that do not use first-past-the-post systems or proportional representation, 2-party systems can also arise. The country of Gibraltar has a 2-party system and uses a partial block vote system, in which there are more positions available than there are votes. As positions go to candidates that receive the most votes, this system makes it difficult for a third party to win elections.

Avoiding a Collapse into a Two Party System

While it is common for a two party system to develop under the plurality vote, there are several proposed methods for reducing this tendency.

Modifying the Standard Plurality System

One solution to avoid the two party system is to incorporate Instant Runoff Voting. With Instant Runoff Voting, voters rank their candidate choices, and if no candidate has the majority of first place votes, then the candidate with the least first place votes is eliminated and the process is repeated until a majority candidate is selected. This system would reduce the influence of tactical voting because voters can trust that if their first choice doesn't win, they will still have influence in the overall outcome. While this would be difficult to implement in an established two party system, it has seen some success in the United States. When implemented in San Francisco City Council elections, it has reduced violations of the Condorcet Rule and increased voter trust in the system (Source: Grofman, B. "Electoral Studies." Volume 23, Issue 4, December 2004).

Another, more drastic change one can make to the election system is known as "proportional representation". Rather than the fairly standard method of electing a single winner to each available seat, PR systems appropriate seats to individual parties based on the proportion of votes they receive. One way this is done, is to have each party list its candidates in some preferred order. Voters then cast votes for entire parties, and each party receives seats based on the number of votes it gets. The actual candidates elected is determined by the list provided by the party. This method is simple, but has the disadvantage that voters cannot vote for individual candidates.

Another PR system is called the "single-transferable vote" method. In this method, voters rank their preferences in order. If a candidate meets some quota of 1st place votes, he is elected, and the votes of the people who ranked him number 1 are transferred to their second choice. If no candidate meets the quota, the last place candidate is eliminated and his 1st place votes are transferred to those voters' second choices. This is repeated until all seats are filled.

Both of these methods avoid suppressing minor parties by getting rid of the idea of "one vote, one winner". Voters never feel like they are casting a "wasted vote", since a parties representation is based on the proportion of votes they receive. So if only 10% of the population supports some party, in a plurality election, that party would get no representation. However, in a PR system, approximately 1 in 10 elected candidates would be from that party.

Third Party Success in a Two Party System

While third parties tend to get absorbed into one of two dominant parties, there are situations when a third party can become a prominent player in the political landscape. This generally happens when a third party can exploit some weakness/mistake of a larger party. This in turn usually occurs in times of great political or social turmoil. For example, in the 19th century, social movements such as slavery and women's suffrage led to the creation of many third parties that focused on these issues. The large portion of citizens that were passionate about these issues allowed these smaller parties to gain traction and get elected officials in some cases. A more lasting example is provided by the undoing of the Whig party during the American Civil War. Due to leadership issues, the Whigs failed to take decisive stances on multiple issues (including slavery), and this allowed the progressive Republican party to take its place [3].

References

[1] http://janda.org/c24/Readings/Duverger/Duverger.htm - An original paper by Duverger describing his law

[2] http://www.jstor.org/stable/1962968 - An analysis of Duverger's Law

[3] http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/essays/1801-1900/the-american-whig-party/the-end-of-the-party.php