Perception of Beauty in The Golden Ratio

Recognizing patterns has been necessary for humans to evolve into humanity as we know it today. One example of these patterns is the golden ratio. This ratio has showed up in many human-made objects, especially in architecture, including the Parthenon, the Notre-Dame of Laon Cathedral, and the Taj Mahal (Mastroeni).

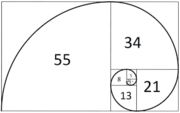

One possible reason we see this show up so often is because of the golden rectangle. The golden rectangle is a rectangle with a side of length X and the other side of length X times phi (1.618…) and iteratively adds lines to create squares. This creates a picture that many people believe is aesthetically pleasing. It also forms a spiral from the quarter circle arcs which is known as the golden spiral. Even today, many architects use this same ratio and rectangle in current designs.

There are very few explanations across many scientific papers that explain why this is the case. One simple explanation for why they do this is because beautiful structures are more likely to be selected by the customer for the design and thus gives them a higher economic payoff. However, a more mathematical explanation is that these rectangles have high adjacency of edges and therefore are considered to be “one of the best the connected rectangular arrangements” (Shekhawat). However, while this may be true, there is little factual evidence to support the idea that ancient architects designed structures with connectivity in mind.

Beauty is something subconscious in our brains that either appeals to us or does not, this subconscious effect occurs because recognizing patterns has kept us safe by helping us react more quickly in life-threatening situations (Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell). The Fibonacci sequence is an example of a real life pattern that occurs in nature that forms the building blocks of the golden ratio which in the limit, as n approach infinity, of F(n+1)/F(n) where F(n) is the n-th number of the Fibonacci sequence.

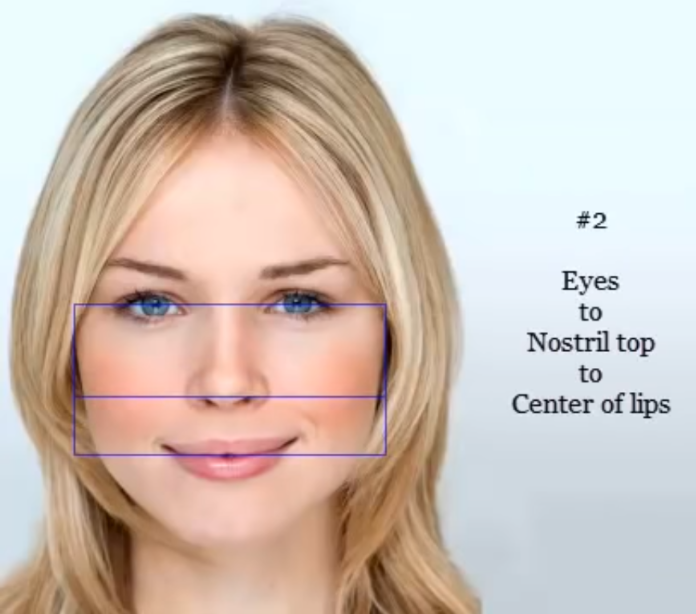

There are many examples of the Fibonacci sequence in real life including sunflowers which have spirals consisting of 34 and 55 seeds in a spiral and even flowers with 89 and 144 seeds in a spiral. Daisies follow the same pattern with respect to their petals (Moore). Interestingly, another example of the golden ratio showing up in nature is in facial features. In a 2012 contest to find the prettiest face in Britain, over 8000 entries were put forth without makeup and one woman stood out. Using a software algorithm to find golden ratios in the face, in the vertical and horizontal direction, 24 golden ratios were identified (Meisner Beauty, the Perfect Face and the Golden Ratio, Featuring Florence Colgate). Conventionally, people find curves attractive. The golden spiral and ratio both create beautiful curves and generate a perfect proportions. Whether or not we fully understand why this ratio shows up so frequently in nature, there is no denying that we are allured to its beauty.

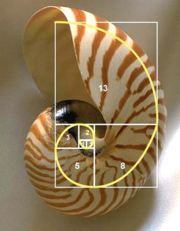

Perhaps some of the most interesting examples of the golden ratio lie in the Fibonacci spiral. The golden spiral shows up in “mollusk shells, ram horns, parrot beaks, elephant tusks, lion claws, comet tails, spider webs, meteor craters, the shoreline of Cape Cod, the shapes of breaking waves and even the spiral galaxies of the universe” (Moore). Clearly, the Fibonacci sequence has a significance in nature that even the brightest minds have yet to determine the meaning behind. In many of these cases it may be coincidence or pure luck. In other cases, it may have been the best outcome of an evolutionary process. Humans have always noticed patterns and used them to guide our way through the universe whether or not they are significant.